News, Reviews, Reports

Sayonara to the Art Space Tokyo Blog

After four years of running the Art Space Tokyo blog, it’s time to bring it to a quiet conclusion.

Activity on this blog has ebbed and flowed over the years. At the beginning we regularly posted reports and reviews, but after a year or two we became busier and busier. From 2009 onward, I usually only had time to post monthly round-ups of links to other people’s articles on Japanese art. Even though I only did them once a month, they were a completely tedious chore, but I was driven by hope that in the long term they would be a valuable resource: a centralized point of reference for what people were writing about Japanese art in the early 21st century. But nowadays I want to focus on other projects and not become bound to something merely for the sake of doing it.

Art Space Tokyo has been one of the most rewarding projects Craig and I have ever worked on. From mid to late 2007, we trekked the city in search of its most unusual galleries and museums and we came to know some of the curious characters who keep the Tokyo art world ticking along. In early 2008, we bound their stories into a book that we envisaged as a work of art in its own right, and we were unbelievably lucky to have it illustrated by one of our favorite artists—the gifted and prolific Nobumasa Takahashi.

Though the book bucked the trend of how the Tokyo art world prefers to present itself (something I wrote about in this essay), the reaction was overwhelmingly positive from the outset. We have met so many people for whom the book has been an invaluable gateway to the Tokyo art world, which can be so hard to figure out when you don’t know where to look.

We were stunned when the first (albeit small) print run was sold out within a year of publication. Without any great expectations, in May 2010 we launched a Kickstarter campaign to raise $15,000 for a reprint and the development of a digital version. Back then, Kickstarter was a completely new model of fundraising, so you can imagine our disbelief as we watched a torrent of contributions push us well past our goal and bring in $24,000. Again, to our backers: thank you, thank you, thank you. We will never forget the buzz at the relaunch party we held at the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art nor the rare spectacle of almost every major figure in the Tokyo art world gathered in one room at TODs Omotesando.

Our experience with Kickstarter prompted Craig to write Kickstartup, the first thorough examination of what makes a successful Kickstarter campaign. These days, you have to pull in a few-million-dollars’ worth of microfunding to catch anyone’s attention, but if you haven’t read Craig’s essay already, it’s worth it to remember what the climate was like back then—only two and a half years ago. From then on, Craig wrote more and more about the state of digital publishing. Books in the Age of the iPad (2010), Post-Artifact Books and Publishing (2011) and Subcompact Publishing (2012) are all essential reading. In only four years, the landscape of digital publishing has shifted so much, and I continue to be humbled by the clarity and reason that Craig brings to a still-nascent and contentious discourse.

Although it took us longer to bring it to you than we originally hoped, in the fall of 2012 we finally launched the promised digital versions of Art Space Tokyo. In keeping with the principle of “pointability” that Craig explains in his accompanying essay Platforming Books, the entire contents of Art Space Tokyo are available on read.artspacetokyo.com. Furthermore, this website offers a greatly expanded timeline of events in the Japanese art world since 1945, as well as extensive appendices of resources on the Japanese art world. Even if it’s only on an occasional basis, I will continue to update the timeline and appendices, and use @ArtSpaceTokyo as a simple way of drawing attention to things that are happening in the world of Japanese modern and contemporary art.

Looking back at the Japanese art world in the past four years, what has changed? In terms of Art Space Tokyo’s function as a guidebook, it is inevitable that its contents will gradually go out of date. Already, Nakaochiai Gallery shut its doors, Project Space Kandada closed and was reborn as 3331 Arts Chiyoda, 101Tokyo Contemporary Art Fair didn’t return after its second year, and Shinwa Art Auction no longer holds significant contemporary art sales in Japan. But I’m reassured by the thought that even if none of the institutions or individuals in Art Space Tokyo are active in 30 years from now, the book’s interviews and essays retain an enduring value as a historical record of the Japanese art world at the end of the 2000s.

In terms of the Japanese art world in general, it is hard to say what changes have taken place in the past four years. In the preface to the second edition I wrote, “…the recession, which caused hundreds of galleries to shut down in other countries, has not affected Tokyo’s art world to the same extent. There was no bubble in the Japanese art market in 2008, so nothing really burst.” While that remains true, now that more time has passed I do detect a more fundamental change than I had previously noticed. In the years before I left Tokyo for New York at the end of 2008, I remember there being a distinct sense of optimism that contemporary Japanese art might just be on the cusp of renewed recognition and that the tepid Japanese art market could only get stronger. However, having returned to Tokyo six months ago, there seems to be an underlying feeling of tired resignation to the status quo. It is understandable: after more than two decades of economic stagnation, the latest global recession is painfully familiar to the Japanese. Moreover, the catastrophic earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear contamination that ensued have all raised serious questions about the government’s competence and honesty, instilling genuine feelings of fear about this country’s future. It is still too early to say how the current climate is affecting Japanese artists, but it isn’t hard to imagine that in the coming years their work might become more cynical.

On a more positive note, there has been a global surge of interest in postwar Japanese art, particularly in the United States. In the past two years, there has been a slew of major museum exhibitions: most notably Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; and Gutai: Splendid Playground at the Guggenheim, New York, opening on February 14. Commercial galleries have also been crucial to this renewed momentum. In New York, Hauser & Wirth recently held A Visual Essay on Gutai and for several years McCaffrey Fine Art has been putting on solid solo exhibitions of Hitoshi Nomura, Kazuo Shiraga, Sadamasa Motonaga, Jiro Takamatsu, and Noriyuki Haraguchi. In Los Angeles, Blum & Poe’s survey Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha last February was instrumental to putting Mono-ha back on the map, and later in the year it was followed by a solo exhibition of Kishio Suga. Susumu Koshimizu’s solo show will start on February 23.

Though this activity is mostly taking place in New York and LA, there have been some crucial shows in Japan: a retrospective of Atsuko Tanaka at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo; Gutai: The Spirit of an Era at the National Art Center, Tokyo; 1968–1982: The 70s in Japan at the Museum of Modern Art, Saitama; and Jikken Kobo – Experimental Workshop at the Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura.

Frankly, the timing of all these developments is an incredible blessing for me, as my original field of specialization was postwar Japanese art, with particular emphasis on Mono-ha. I’m now working for Blum & Poe as the director of their forthcoming Tokyo space, details of which will be made public in the coming months. In the meantime, there is a huge amount of archival work that has to be done for the Mono-ha artists. This is what I am focused on these days. Likewise, Craig is cooking up all kinds of new things.

So, with a lot of nostalgia about the creation of Art Space Tokyo and pride about its life in the wild, Craig and I want to say once more how thankful we are to all our readers and supporters. We wish you a very happy 2013 and hope you make amazing books!

If you want to keep up with what Craig and I get up to, it’s all at craigmod.com and ashley.rawlings.com.

DECEMBER ARTICLE ROUND-UP

Every month, Art Space Tokyo offers you a round up of exhibition reviews, interviews, feature articles and news items published on other websites. For up-to-the-minute info on Japanese contemporary art, follow us on Twitter.

Reviews

• “Tokyo Art Meeting III: Art and Music — Search for New Synesthesia” at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo [ArtAsiaPacific]

• Kishio Suga at Blum & Poe, Los Angeles [Artforum]

• “Pop-Up Mathaf” at the Mori Art Museum [ART iT]

• “How Physical” at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography [ART iT]

• Tadanori Yokoo at the Yokoo Tadanori Museum of Contemporary Art [Artscape International]

• Tadanori Yokoo at the Yokoo Tadanori Museum of Contemporary Art [Japan Times]

• Hideki Nakazawa at the Kichijoji Art Museum [Japan Times]

• Ben Shahn at the Museum of Modern Art, Saitama [Japan Times]

• Kishin Shinoyama at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery [Japan Times]

• Taiji Matsue at the Izu Photo Museum [Japan Times]

• “Tokyo Designers Week” at Jingu-Gaien Kaigakukanmae [TAB]

• “Tokyo Photo 2012” at Tokyo Midtown Hall [TAB]

• Makoto Aida at the Mori Art Museum [TAB]

• FILMeX 2012 [TAB]

News

• Japanese Architects lead M+ Shortlist [ART iT]

• Shizuko Watari (1932–2012) [ART iT]

• Yasumasa Morimura to direct Yokohama Triennale 2014 [ART iT]

• Japan’s museums enjoy a makeover [Japan Times]

• A Year of Art News in Japan [TAB]

• 2012: The Year in Review [TAB]

NOVEMBER ARTICLE ROUND-UP

Every month, Art Space Tokyo offers you a round up of exhibition reviews, interviews, feature articles and news items published on other websites. For up-to-the-minute info on Japanese contemporary art, follow us on Twitter.

Reviews

• “The Long Residence: At Home Again” at the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art [Artscape International]

• Ikko Tanaka at 21_21 Design Sight [Japan Times]

• David Lynch at the LaForet Museum [Japan Times]

Interviews and Features

• Naoshima [ArtAsiaPacific]

• Daido Moriyama: Stray Dog of Tokyo [ArtAsiaPacific]

• Koki Tanaka [ART iT]

• Masato Nakamura [Japan Times]

OCTOBER ARTICLE ROUND-UP

Every month, Art Space Tokyo offers you a round up of exhibition reviews, interviews, feature articles and news items published on other websites. For up-to-the-minute info on Japanese contemporary art, follow us on Twitter.

Reviews

• Daido Moriyama at BLD Gallery [Artscape International]

• Studio Mumbai at the Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo [Artscape International]

• Chim↑Pom at the Parco Museum [TAB]

Features

• Actuality and Art I [Realtokyo]

News

• Takashi Azumaya (1968–2012) [ART iT]

SEPTEMBER ARTICLE ROUND-UP

Every month, Art Space Tokyo offers you a round up of exhibition reviews, interviews, feature articles and news items published on other websites. For up-to-the-minute info on Japanese contemporary art, follow us on Twitter.

Reviews

• Takeshi Murata at Salon 94, New York [Art in America]

• Peter Bellars at 3331 Arts Chiyoda [Artscape International]

• “Gutai: The Spirit of an Era at the National Art Center, Tokyo [Frieze]

• Naoya Hatakeyama at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art [LA Times]

• Tatzu Nishi at Columbus Circle, New York [NY Times]

• Tatzu Nishi at Columbus Circle, New York [Spoon & Tamago]

• Hiroshi Fuji at 3331 Arts Chiyoda [Spoon & Tamago]

Interviews and Features

• Observations on Japanese Cinema After 3/11 [film.culture.360]

• Tatzu Nishi [NY Times]

• Mr at Lehmann Maupin, New York [VernissageTV]

• MoMAT Pavilion by Studio Mumbai at the Museum of Modern Art Tokyo [Vimeo]

News

• Takashi Azumaya (1968–2012) [ART iT]

• Japanese galleries open in the Gillman Barracks in Singapore [ART iT]

• Japanese galleries open in the Gillman Barracks in Singapore [Japan Times]

• Blum & Poe announces plans to open Tokyo Office [LA Times]

• Blum & Poe announces plans to open Tokyo Office [The Art Newspaper]

Genron and Shisouchizu Beta — Japan 2.0

Sometimes a close friend more or less disappears off the map for a couple of years. Only sporadic email contact assures you they’re still breathing. This is how it has been with my very talented friend Naoki Matsuyama. Here are some samples from the relatively few emails Naoki has sent me in the past year:

It’s so busy right now that I haven’t got time to think about anything else.

Gmail is telling me that it took me 14 days to reply to your email. I’m mortified. I had a couple of big business trips and a transition to a new company structure and I really couldn’t think about anything else.

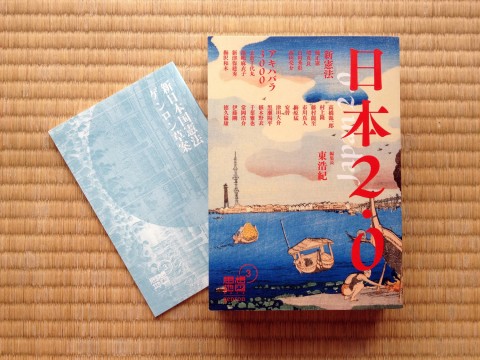

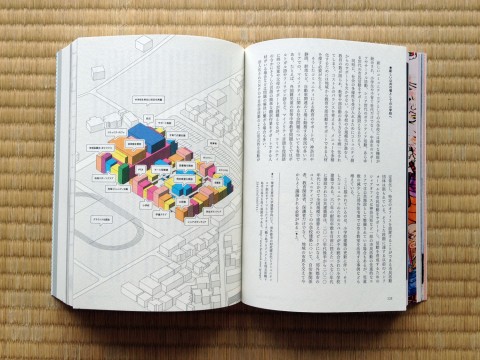

What Naoki has been thinking about so intensely is his work as an editor at Genron, a publishing company behind the annual, high-quality journal Shisouchizu Beta, which attempts to rethink what direction this country should take in the 21st century, especially in the aftermath of March 11, 2011.

Established in Tokyo in 2010 by critic and author Hiroki Azuma, Genron is an English-based web portal for critical discourse on Japan. Its editorial mission reflects on how, in the second half of the 20th century, Japanese society underwent major political and cultural shifts that propelled have made it a huge exporter of technology and pop culture, and yet its intellectual discourse remains little known abroad.

It also focuses on the significant turning point that Japan finds itself at today, faced with issues of decline and regeneration in the immediate future. Genron posits that “For the next 5 to 10 years, Japan will become a sort of testing ground for diverse political, social and cultural undertakings. We believe that persistently sending out messages from this “site for testing” to English speaking readers beyond the Japanese speaking world, will be of benefit not only to some researchers and fans, but also to the general public. “genron” starts as a website for presenting Japanese critical discourses, but it is not limited to that and is in fact potentially intended for anyone who thinks about the new societies and cultures of the 21st century.”

When Naoki and I finally sat down to dinner a couple of weeks ago and he handed me a copy of the latest issue of Shisouchizu Beta, entitled “Japan 2.0,” it was immediately evident to me why he had been so busy. It’s a thick publication, with 515 pages of Japanese articles and 113 pages of (excellent) English translations and abstracts. Great attention has been paid to the quality and diversity of design and paper stock, making this a very handsome book indeed.

With article titles ranging from “Plan 2.0 for Remodeling the Japanese Archipelago” to “The Disempowered Japanese Provinces – Is Consumer Society an Enemy of Democracy?” the current issue contains some hard-hitting words that are reminiscent of Japan’s 1960s and ‘70s leftwing radicalism. There is an interview with Takeshi Umehara, a Kyoto-based philosopher who believes that the Fukushima nuclear accident was nothing short of a “civilizational disaster.” There is also a transcript of Takashi Murakami’s speech at the opening of his “Murakami – Ego” exhibition at Mathaf in Doha earlier this year, in which he counters the criticisms people have made of his mass-produced approach to art-making and reasserts his long-held belief that Japanese people have to rid themselves of their “softness” if they are to fulfill their true potential.

Perhaps the most insightful article is a conversation on the future of journalism—mainly in the Chinese context—between China- and Japan-based journalists Michael Anti, Daisuke Tsuda and Hiroki Azuma. Among the various topics they discuss, Anti explains how, with no short-term political agenda to adhere to, Chinese reporters sent to cover the post-3/11 recovery for more protracted periods of time were fully able to see the humanity of their subjects. Impressed by the relief effort (especially in contrast to the Chinese government’s handling of the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake), they left Japan with highly favorable impressions that they then relayed to their readers. This was heartening to read, yet at the same time, utterly depressing in light of the recent territorial dispute over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, which has so quickly undone all of that bridge-building. It takes months, years, even decades to build trust between two mutually suspicious societies, but in only a matter of hours their politicians and other extremist elements can force everybody back to square one through nationalistic posturing and fear-mongering.

The issue also contains a pull-out supplement, Genron’s draft for a new Japanese constitution. Among various things, this proposal calls for recognition that “in the future, Japanese culture will not solely belong to Japan, and different cultures will in turn flow into Japan.”

AUGUST ARTICLE ROUND-UP

Every month, Art Space Tokyo offers you a round up of exhibition reviews, interviews, feature articles and news items published on other websites. For up-to-the-minute info on Japanese contemporary art, follow us on Twitter.

Reviews

• Ai Yamaguchi and Pip & Pop at Spiral Garden [ArtAsiaPacific]

• Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale at various venues in Niigata [Artforum]

• “Gutai: The Spirit of an Era” at the National Art Center, Tokyo [Artforum]

• Masako Ando at the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art [Artforum]

• Yoko Ono at the Serpentine Gallery, London [Artforum]

• “Gutai: The Spirit of an Era” at the National Art Center, Tokyo [Artscape International]

• “Tema Hima: The Art of Living in Tohoku” at 21_21 Design Sight [Artscape International]

• Takayuki Yamamoto at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco & the Takamatsu City Museum of Art [Artscape International]

• Yoko Ono at the Serpentine Gallery, London [Artwrit]

• Simon Fujiwara at Tate St Ives [Frieze]

• Tomoyoshi Murayama at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto [Frieze]

• Hideki Nakajima at the Daiwa Press Viewing Room, Hiroshima [Japan Times]

• “The Cosmos as Metaphor” at Taka Ishii Gallery, Kyoto & Hotel Anteroom, Kyoto [Japan Times]

• Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale at various venues in Niigata [Japan Times]

• Andrew Burns and Brook Andrew at the Australia House in the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale [Japan Times]

• “Real Japanesque: The Unique World of Japanese Contemporary Art” at the National Museum of Art, Osaka [Japan Times]

• Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale at various venues in Niigata [Spoon & Tamago]

• “Gutai: The Spirit of an Era” at the National Art Center, Tokyo [Wall Street Journal]

Interviews

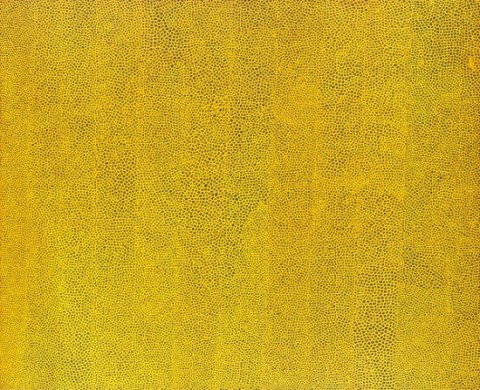

• Yayoi Kusama [ART iT]

• Yayoi Kusama [Huffington Post]

• Naoya Hatakeyama [SF Gate]

Features

• Collector Daisuke Miyatsu [Artinfo]

• Daido Moriyama’s color photographs [ART iT]

• Nobuyoshi Araki [Huffington Post]

• Yoko Ono and Kenji Yanobe at the Contemporary Art Biennale of Fukushima [Japan Times]

• “Tokyo 1955–1970” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York [Japan Times]

• Yukinori Yanagi’s Banzai Corner [Spoon & Tamago]

News

• Nara as Businessman (Original blog post) [Adrian Favell’s blog on ART iT]

• Yoshitomo Nara’s list of objections to Favell’s text (English) [ART iT]

• Yoshitomo Nara’s list of objections to Favell’s text (Japanese) [ART iT]

• Tetsuya Ozaki’s commentary on Favell/Nara dispute (Japanese) [Realtokyo]

• Toyo Ito’s Japan Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale awarded best pavilion [Designboom]

Reconsidering the Historical Pantheon

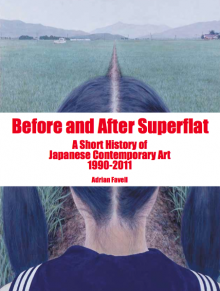

A review of Before and After Superflat: A Short History of Japanese Contemporary Art 1990–2011. By Adrian Favell, Blue Kingfisher Limited, 2012; 246 pages.

The boom in Japan’s pop culture during the 1990s and 2000s was a mixed blessing, both advancing and encumbering the country’s reputation abroad. With global enthusiasm for anime and manga carrying over into the art world, this Zeitgeist for all things kawaii (cute) and kowakawaii (creepy cute) was crucial to fueling the popularity of artists such as Takashi Murakami, Yoshitomo Nara and Mariko Mori. Yet, manga and anime’s commercial success in the United States and Europe belies the drastic but little-known decline of these industries at home, and the enormous prominence of Murakami, Nara and Mori’s work on the international stage—while inspiring many—has also inevitably distracted from the wider range of ideas being explored by other artists in Japan.

The boom in Japan’s pop culture during the 1990s and 2000s was a mixed blessing, both advancing and encumbering the country’s reputation abroad. With global enthusiasm for anime and manga carrying over into the art world, this Zeitgeist for all things kawaii (cute) and kowakawaii (creepy cute) was crucial to fueling the popularity of artists such as Takashi Murakami, Yoshitomo Nara and Mariko Mori. Yet, manga and anime’s commercial success in the United States and Europe belies the drastic but little-known decline of these industries at home, and the enormous prominence of Murakami, Nara and Mori’s work on the international stage—while inspiring many—has also inevitably distracted from the wider range of ideas being explored by other artists in Japan.

In spite of the abundance of monographs on these three artists (and a handful of other globally recognized contemporary artists such as Hiroshi Sugimoto), there are very few publications in English that survey the broader context that surrounds them. With Before and After Superflat: A Short History of Japanese Contemporary Art 1990–2011, Adrian Favell, then a Professor of Sociology at UCLA, aims to fill this gap. Invited to Tokyo as a Japan Foundation Abe Fellow in 2007, Favell spent that year and several subsequent visits spending time with dozens of artists, dealers, curators, collectors, critics, and other figures. Woven together from the multiplicity of their subjective perspectives as much as recourse to black-and-white documentable sources, the book is the product of his ethnographic/observational sense of the art scene—similar in approach to Sarah Thornton’s Seven Days in the Art World (2008). Though limited to some extent by his reliance on art-world insiders as guides and translators, as a self-professed “outsider” he has more freedom to adopt the kind of candid criticality that most people in the Japanese art world would be too wary to express in public for fear of being perceived as unsupportive.

For the first third of the book, Favell reflects on how the birth of Murakami, Nara and Mori’s practices were the product of a pre-2008 mentality in which artists had to massively increase their production values in order to achieve international recognition. The author focuses particularly on Murakami and Nara as the most consequential of the three, and analyzes their business strategies. On the one hand, Murakami, who was dissatisfied with the “lame art education, the exploitative galleries, the parochial debates, the ineffective market, and the claustrophobic schools,” sought to rebuild the Japanese art world in his own image. Adopting a top-down corporate approach, he set up his own Warhol/Koons/Hirst-style production company Kaikai Kiki, collaborated with real-estate tycoon Minoru Mori on the branding for his Mori Art Museum and the luxury mixed-use complex that houses it, and established GEISAI, a large biannual festival-cum-talent show in which participants apply and pay for a booth to show their work.

For the first third of the book, Favell reflects on how the birth of Murakami, Nara and Mori’s practices were the product of a pre-2008 mentality in which artists had to massively increase their production values in order to achieve international recognition. The author focuses particularly on Murakami and Nara as the most consequential of the three, and analyzes their business strategies. On the one hand, Murakami, who was dissatisfied with the “lame art education, the exploitative galleries, the parochial debates, the ineffective market, and the claustrophobic schools,” sought to rebuild the Japanese art world in his own image. Adopting a top-down corporate approach, he set up his own Warhol/Koons/Hirst-style production company Kaikai Kiki, collaborated with real-estate tycoon Minoru Mori on the branding for his Mori Art Museum and the luxury mixed-use complex that houses it, and established GEISAI, a large biannual festival-cum-talent show in which participants apply and pay for a booth to show their work.

On the other hand, though Nara eschews such a bombastic approach to business, Favell argues that his “slacker CEO” demeanor belies an equally calculating strategy of populist outreach in which he not only sells his paintings and sculptures to top collectors but also churns out a vast range of more affordable merchandise that has appealed to fad-obsessed hipsters the world over. Favell paints an unfavorable picture of Nara building his indie reputation off the back of “collaboration” with thousands of fans who helped construct the ramshackle, shed-like installations of his A to Z series of touring exhibitions.

While acknowledging the positive interest Murakami and Nara’s work stirred abroad, Favell concludes this section with a stark assessment of the resentment that their upending of the status quo stirred at home. In retrospect, GEISAI “undercut the efforts of galleries to build sustainable value on emerging artists’ works” and “distracted the attention of the global art media away from serious Japanese art.” Most damning of all, the author states that “GEISAI removed the need for serious art education and filled young heads full of illusionary dreams,” and posits that Nara’s “community” was little more than “a temporary refuge from reality, where costless volunteers were put to work for an artist’s brand . . . Now Cool Japan is over. Murakami and Nara’s children have nowhere to go.”

The chapter on Nara, which Favell published as an extract on his ART iT blog, recently triggered a backlash from the artist, who disputed the accuracy of numerous points. Though there are certainly factual and contextual inaccuracies (a full list of the disputed points and Nara’s responses can be found on ART iT in English and Japanese), a significant part of the controversy was fueled by the imperfect translation that Favell posted with the original text. Favell’s writing style is strewn with casual metaphors and, in an attempt to give some narrative vigor to his account of the art world, often reads as sarcastic. Writing of this kind is very difficult to translate into Japanese without sounding rude and aggressive, and some of his metaphors were rendered too literally, giving rise to further misunderstandings. Lastly, Favell’s decision not to use footnotes and rely instead on an index of the people he conversed with as his list of sources also leaves him open to attack when the facts come into question.

[Disclosure: As of August 2012, I am the director of the Tokyo Office of Blum & Poe, Murakami and Nara’s gallery in Los Angeles.]

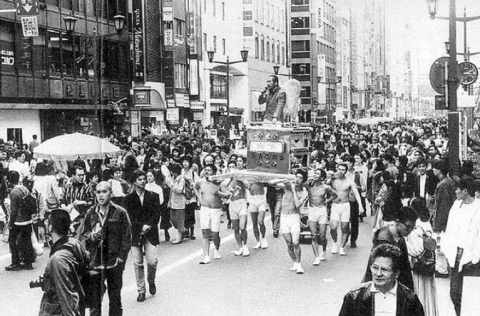

The rest of the book shifts to a discussion of developments that have been overlooked during the past two decades. In particular, Favell examines the generation of artists who came of age during the mid-1980s, such as Makoto Aida, Parco Kinoshita, Hiroyuki Matsukage, Oscar Oiwa, Tsuyoshi Ozawa and Yutaka Sone (collectively known as the original members of the Showa 40 nen kai, or “Group 1965,” named after the year of their birth), as well as Kenji Yanobe, Miwa Yanagi, Yukinori Yanagi, Masato Nakamura and the commandN collective. Like Murakami, these artists were frustrated by the limitations of the Japanese scene—especially the dominance of the expensive rental gallery system—but rather than create new, slick brands of their own they responded with rough, neo-Dadaist absurdism, including guerilla interventions in public space.

Favell pays special attention to Makoto Aida, who after years of being a cult figure in Japan is only now receiving serious recognition with a retrospective at the Mori Art Museum in November. The author champions Aida as a true provocateur who is unafraid to broach historical and social taboos, on a par with Jake and Dinos Chapman and deserving of comparable recognition yet ignored by the art world outside of Asia. He attributes the slowness of Aida’s rise in part to his dealer Sueo Mitsuma’s decision to maintain exclusive representation of his artists rather than develop “quid pro quo international networks”—a strategy that has benefitted gallerists such as Tomio Koyama, Masami Shiraishi and Atsuko Koyanagi. Likewise, many of their most successful artists—among them Tatsuo Miyajima and Hiroshi Sugimoto—are international networkers in their own right. As Favell puts it, “Mitsuma was evidently betting on the long run. But it is still not clear that any Japanese artist can do without the gaisen kouen (triumphant return performance) if they want to make it to the historical pantheon.”

In this vein, much of Before and After Superflat is depressingly pessimistic, albeit not without reason. Favell dwells on several missed opportunities, such as the mismanagement of the second and third Yokohama Triennales in 2005 and 2008, which by failing to capitalize on the achievements of the first edition cost Japan a crucial chance to reassert itself in a regional scene now dominated by the biennales in China, Taiwan, Korea, Singapore and Australia. Likewise, he laments the ill-fated mix of pork barrel spending and underfunding of museums, using the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa as a prime example of how smaller cities have been lumbered with institutions that are beautifully designed yet lack sufficient funding for top-quality acquisitions and exhibition planning. By contrast, the author does express hope for the future of rural events such as the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale and the Setouchi International Art Festival. Though not without their flaws, these “slower,” more community-based endeavors, focused on the conservation and renovation of traditional buildings as sites for art display, are more inherently sustainable—the antithesis of the dystopian corporate approach to the arts that led to the Mori Art Museum and its surrounding complex being branded as an “artelligent city.”

For the most part, Favell’s survey of recent developments in Japanese art is successful. At times, however, the narrative is long-winded and repetitious, frustratingly vague about dates and locations, and the breeziness of its tone can irritate. The author is prone to making sweeping statements, and the four pages he allocates to comparing the Japanese and Chinese art scenes—two vastly different contexts—are the weakest part of the book. There is also a handful of bizarre omissions. Taka Ishii is as important a gallerist as Mitsuma, Koyama, Shiraishi and Koyanagi, but he is referred to only once in passing, and in a passage that describes the prominence of young female dealers in the “New Tokyo Contemporaries” association of seven emerging galleries, half of those women (Atsuko Ninagawa, Misako Rosen and Yuka Sasahara) go without mention. As with some of the issues Nara raises in his list of complaints on ART iT, lapses of this kind have the unfortunate effect of casting doubt over the thoroughness of the rest of the text. Lastly, the final chapter only touches on a small number of artists born after 1975, such as Tabaimo, Koki Tanaka, Teppei Kaneuji and the Chim↑Pom collective. After being given so much detail about their predecessors, one is left wanting more.

Regardless, the full range of contemporary Japanese art remains woefully underrepresented on the international stage, and Favell has taken an important step toward rectifying that discrepancy. He plans to follow it with a more academic publication on post-bubble festivals and innovations in art and architecture in relation to regional and urban development. In spite of the book’s flaws, for those who seek a critical reflection on Japan’s most prominent artists since 1990 as well as a primer on the work of their lesser-known peers and successors, Before and After Superflat is a worthwhile start.

About & Community

A place to keep abreast of Art Space Tokyo related news, reviews, events and updates.

Art Space Tokyo is a 272 page guide to the Tokyo art world produced and published by Craig Mod & PRE/POST.

It was originally published in 2008 by Chin Music Press.

Current Tokyo exhibitions

Powered by Tokyo Art Beat