Books & Magazines

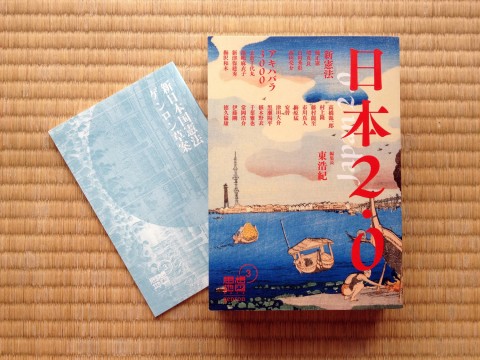

Genron and Shisouchizu Beta — Japan 2.0

Sometimes a close friend more or less disappears off the map for a couple of years. Only sporadic email contact assures you they’re still breathing. This is how it has been with my very talented friend Naoki Matsuyama. Here are some samples from the relatively few emails Naoki has sent me in the past year:

It’s so busy right now that I haven’t got time to think about anything else.

Gmail is telling me that it took me 14 days to reply to your email. I’m mortified. I had a couple of big business trips and a transition to a new company structure and I really couldn’t think about anything else.

What Naoki has been thinking about so intensely is his work as an editor at Genron, a publishing company behind the annual, high-quality journal Shisouchizu Beta, which attempts to rethink what direction this country should take in the 21st century, especially in the aftermath of March 11, 2011.

Established in Tokyo in 2010 by critic and author Hiroki Azuma, Genron is an English-based web portal for critical discourse on Japan. Its editorial mission reflects on how, in the second half of the 20th century, Japanese society underwent major political and cultural shifts that propelled have made it a huge exporter of technology and pop culture, and yet its intellectual discourse remains little known abroad.

It also focuses on the significant turning point that Japan finds itself at today, faced with issues of decline and regeneration in the immediate future. Genron posits that “For the next 5 to 10 years, Japan will become a sort of testing ground for diverse political, social and cultural undertakings. We believe that persistently sending out messages from this “site for testing” to English speaking readers beyond the Japanese speaking world, will be of benefit not only to some researchers and fans, but also to the general public. “genron” starts as a website for presenting Japanese critical discourses, but it is not limited to that and is in fact potentially intended for anyone who thinks about the new societies and cultures of the 21st century.”

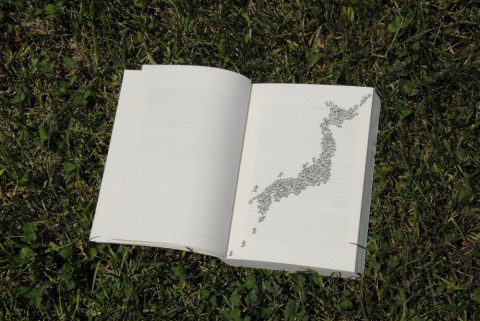

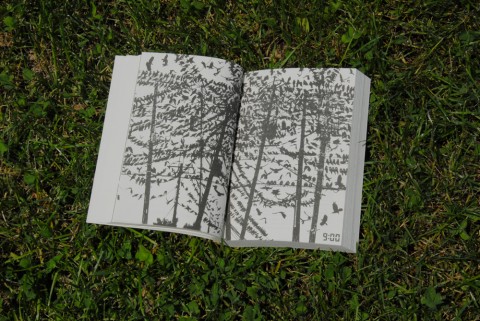

When Naoki and I finally sat down to dinner a couple of weeks ago and he handed me a copy of the latest issue of Shisouchizu Beta, entitled “Japan 2.0,” it was immediately evident to me why he had been so busy. It’s a thick publication, with 515 pages of Japanese articles and 113 pages of (excellent) English translations and abstracts. Great attention has been paid to the quality and diversity of design and paper stock, making this a very handsome book indeed.

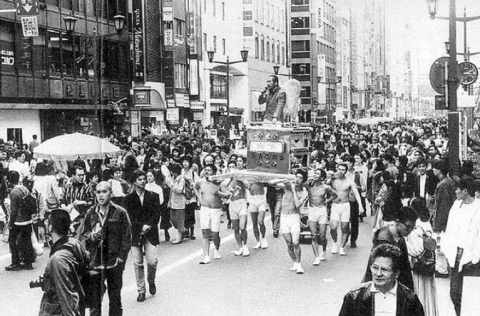

With article titles ranging from “Plan 2.0 for Remodeling the Japanese Archipelago” to “The Disempowered Japanese Provinces – Is Consumer Society an Enemy of Democracy?” the current issue contains some hard-hitting words that are reminiscent of Japan’s 1960s and ‘70s leftwing radicalism. There is an interview with Takeshi Umehara, a Kyoto-based philosopher who believes that the Fukushima nuclear accident was nothing short of a “civilizational disaster.” There is also a transcript of Takashi Murakami’s speech at the opening of his “Murakami – Ego” exhibition at Mathaf in Doha earlier this year, in which he counters the criticisms people have made of his mass-produced approach to art-making and reasserts his long-held belief that Japanese people have to rid themselves of their “softness” if they are to fulfill their true potential.

Perhaps the most insightful article is a conversation on the future of journalism—mainly in the Chinese context—between China- and Japan-based journalists Michael Anti, Daisuke Tsuda and Hiroki Azuma. Among the various topics they discuss, Anti explains how, with no short-term political agenda to adhere to, Chinese reporters sent to cover the post-3/11 recovery for more protracted periods of time were fully able to see the humanity of their subjects. Impressed by the relief effort (especially in contrast to the Chinese government’s handling of the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake), they left Japan with highly favorable impressions that they then relayed to their readers. This was heartening to read, yet at the same time, utterly depressing in light of the recent territorial dispute over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, which has so quickly undone all of that bridge-building. It takes months, years, even decades to build trust between two mutually suspicious societies, but in only a matter of hours their politicians and other extremist elements can force everybody back to square one through nationalistic posturing and fear-mongering.

The issue also contains a pull-out supplement, Genron’s draft for a new Japanese constitution. Among various things, this proposal calls for recognition that “in the future, Japanese culture will not solely belong to Japan, and different cultures will in turn flow into Japan.”

Reconsidering the Historical Pantheon

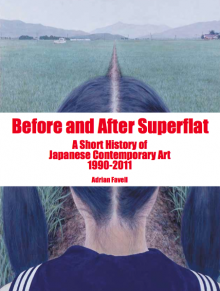

A review of Before and After Superflat: A Short History of Japanese Contemporary Art 1990–2011. By Adrian Favell, Blue Kingfisher Limited, 2012; 246 pages.

The boom in Japan’s pop culture during the 1990s and 2000s was a mixed blessing, both advancing and encumbering the country’s reputation abroad. With global enthusiasm for anime and manga carrying over into the art world, this Zeitgeist for all things kawaii (cute) and kowakawaii (creepy cute) was crucial to fueling the popularity of artists such as Takashi Murakami, Yoshitomo Nara and Mariko Mori. Yet, manga and anime’s commercial success in the United States and Europe belies the drastic but little-known decline of these industries at home, and the enormous prominence of Murakami, Nara and Mori’s work on the international stage—while inspiring many—has also inevitably distracted from the wider range of ideas being explored by other artists in Japan.

The boom in Japan’s pop culture during the 1990s and 2000s was a mixed blessing, both advancing and encumbering the country’s reputation abroad. With global enthusiasm for anime and manga carrying over into the art world, this Zeitgeist for all things kawaii (cute) and kowakawaii (creepy cute) was crucial to fueling the popularity of artists such as Takashi Murakami, Yoshitomo Nara and Mariko Mori. Yet, manga and anime’s commercial success in the United States and Europe belies the drastic but little-known decline of these industries at home, and the enormous prominence of Murakami, Nara and Mori’s work on the international stage—while inspiring many—has also inevitably distracted from the wider range of ideas being explored by other artists in Japan.

In spite of the abundance of monographs on these three artists (and a handful of other globally recognized contemporary artists such as Hiroshi Sugimoto), there are very few publications in English that survey the broader context that surrounds them. With Before and After Superflat: A Short History of Japanese Contemporary Art 1990–2011, Adrian Favell, then a Professor of Sociology at UCLA, aims to fill this gap. Invited to Tokyo as a Japan Foundation Abe Fellow in 2007, Favell spent that year and several subsequent visits spending time with dozens of artists, dealers, curators, collectors, critics, and other figures. Woven together from the multiplicity of their subjective perspectives as much as recourse to black-and-white documentable sources, the book is the product of his ethnographic/observational sense of the art scene—similar in approach to Sarah Thornton’s Seven Days in the Art World (2008). Though limited to some extent by his reliance on art-world insiders as guides and translators, as a self-professed “outsider” he has more freedom to adopt the kind of candid criticality that most people in the Japanese art world would be too wary to express in public for fear of being perceived as unsupportive.

For the first third of the book, Favell reflects on how the birth of Murakami, Nara and Mori’s practices were the product of a pre-2008 mentality in which artists had to massively increase their production values in order to achieve international recognition. The author focuses particularly on Murakami and Nara as the most consequential of the three, and analyzes their business strategies. On the one hand, Murakami, who was dissatisfied with the “lame art education, the exploitative galleries, the parochial debates, the ineffective market, and the claustrophobic schools,” sought to rebuild the Japanese art world in his own image. Adopting a top-down corporate approach, he set up his own Warhol/Koons/Hirst-style production company Kaikai Kiki, collaborated with real-estate tycoon Minoru Mori on the branding for his Mori Art Museum and the luxury mixed-use complex that houses it, and established GEISAI, a large biannual festival-cum-talent show in which participants apply and pay for a booth to show their work.

For the first third of the book, Favell reflects on how the birth of Murakami, Nara and Mori’s practices were the product of a pre-2008 mentality in which artists had to massively increase their production values in order to achieve international recognition. The author focuses particularly on Murakami and Nara as the most consequential of the three, and analyzes their business strategies. On the one hand, Murakami, who was dissatisfied with the “lame art education, the exploitative galleries, the parochial debates, the ineffective market, and the claustrophobic schools,” sought to rebuild the Japanese art world in his own image. Adopting a top-down corporate approach, he set up his own Warhol/Koons/Hirst-style production company Kaikai Kiki, collaborated with real-estate tycoon Minoru Mori on the branding for his Mori Art Museum and the luxury mixed-use complex that houses it, and established GEISAI, a large biannual festival-cum-talent show in which participants apply and pay for a booth to show their work.

On the other hand, though Nara eschews such a bombastic approach to business, Favell argues that his “slacker CEO” demeanor belies an equally calculating strategy of populist outreach in which he not only sells his paintings and sculptures to top collectors but also churns out a vast range of more affordable merchandise that has appealed to fad-obsessed hipsters the world over. Favell paints an unfavorable picture of Nara building his indie reputation off the back of “collaboration” with thousands of fans who helped construct the ramshackle, shed-like installations of his A to Z series of touring exhibitions.

While acknowledging the positive interest Murakami and Nara’s work stirred abroad, Favell concludes this section with a stark assessment of the resentment that their upending of the status quo stirred at home. In retrospect, GEISAI “undercut the efforts of galleries to build sustainable value on emerging artists’ works” and “distracted the attention of the global art media away from serious Japanese art.” Most damning of all, the author states that “GEISAI removed the need for serious art education and filled young heads full of illusionary dreams,” and posits that Nara’s “community” was little more than “a temporary refuge from reality, where costless volunteers were put to work for an artist’s brand . . . Now Cool Japan is over. Murakami and Nara’s children have nowhere to go.”

The chapter on Nara, which Favell published as an extract on his ART iT blog, recently triggered a backlash from the artist, who disputed the accuracy of numerous points. Though there are certainly factual and contextual inaccuracies (a full list of the disputed points and Nara’s responses can be found on ART iT in English and Japanese), a significant part of the controversy was fueled by the imperfect translation that Favell posted with the original text. Favell’s writing style is strewn with casual metaphors and, in an attempt to give some narrative vigor to his account of the art world, often reads as sarcastic. Writing of this kind is very difficult to translate into Japanese without sounding rude and aggressive, and some of his metaphors were rendered too literally, giving rise to further misunderstandings. Lastly, Favell’s decision not to use footnotes and rely instead on an index of the people he conversed with as his list of sources also leaves him open to attack when the facts come into question.

[Disclosure: As of August 2012, I am the director of the Tokyo Office of Blum & Poe, Murakami and Nara’s gallery in Los Angeles.]

The rest of the book shifts to a discussion of developments that have been overlooked during the past two decades. In particular, Favell examines the generation of artists who came of age during the mid-1980s, such as Makoto Aida, Parco Kinoshita, Hiroyuki Matsukage, Oscar Oiwa, Tsuyoshi Ozawa and Yutaka Sone (collectively known as the original members of the Showa 40 nen kai, or “Group 1965,” named after the year of their birth), as well as Kenji Yanobe, Miwa Yanagi, Yukinori Yanagi, Masato Nakamura and the commandN collective. Like Murakami, these artists were frustrated by the limitations of the Japanese scene—especially the dominance of the expensive rental gallery system—but rather than create new, slick brands of their own they responded with rough, neo-Dadaist absurdism, including guerilla interventions in public space.

Favell pays special attention to Makoto Aida, who after years of being a cult figure in Japan is only now receiving serious recognition with a retrospective at the Mori Art Museum in November. The author champions Aida as a true provocateur who is unafraid to broach historical and social taboos, on a par with Jake and Dinos Chapman and deserving of comparable recognition yet ignored by the art world outside of Asia. He attributes the slowness of Aida’s rise in part to his dealer Sueo Mitsuma’s decision to maintain exclusive representation of his artists rather than develop “quid pro quo international networks”—a strategy that has benefitted gallerists such as Tomio Koyama, Masami Shiraishi and Atsuko Koyanagi. Likewise, many of their most successful artists—among them Tatsuo Miyajima and Hiroshi Sugimoto—are international networkers in their own right. As Favell puts it, “Mitsuma was evidently betting on the long run. But it is still not clear that any Japanese artist can do without the gaisen kouen (triumphant return performance) if they want to make it to the historical pantheon.”

In this vein, much of Before and After Superflat is depressingly pessimistic, albeit not without reason. Favell dwells on several missed opportunities, such as the mismanagement of the second and third Yokohama Triennales in 2005 and 2008, which by failing to capitalize on the achievements of the first edition cost Japan a crucial chance to reassert itself in a regional scene now dominated by the biennales in China, Taiwan, Korea, Singapore and Australia. Likewise, he laments the ill-fated mix of pork barrel spending and underfunding of museums, using the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa as a prime example of how smaller cities have been lumbered with institutions that are beautifully designed yet lack sufficient funding for top-quality acquisitions and exhibition planning. By contrast, the author does express hope for the future of rural events such as the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale and the Setouchi International Art Festival. Though not without their flaws, these “slower,” more community-based endeavors, focused on the conservation and renovation of traditional buildings as sites for art display, are more inherently sustainable—the antithesis of the dystopian corporate approach to the arts that led to the Mori Art Museum and its surrounding complex being branded as an “artelligent city.”

For the most part, Favell’s survey of recent developments in Japanese art is successful. At times, however, the narrative is long-winded and repetitious, frustratingly vague about dates and locations, and the breeziness of its tone can irritate. The author is prone to making sweeping statements, and the four pages he allocates to comparing the Japanese and Chinese art scenes—two vastly different contexts—are the weakest part of the book. There is also a handful of bizarre omissions. Taka Ishii is as important a gallerist as Mitsuma, Koyama, Shiraishi and Koyanagi, but he is referred to only once in passing, and in a passage that describes the prominence of young female dealers in the “New Tokyo Contemporaries” association of seven emerging galleries, half of those women (Atsuko Ninagawa, Misako Rosen and Yuka Sasahara) go without mention. As with some of the issues Nara raises in his list of complaints on ART iT, lapses of this kind have the unfortunate effect of casting doubt over the thoroughness of the rest of the text. Lastly, the final chapter only touches on a small number of artists born after 1975, such as Tabaimo, Koki Tanaka, Teppei Kaneuji and the Chim↑Pom collective. After being given so much detail about their predecessors, one is left wanting more.

Regardless, the full range of contemporary Japanese art remains woefully underrepresented on the international stage, and Favell has taken an important step toward rectifying that discrepancy. He plans to follow it with a more academic publication on post-bubble festivals and innovations in art and architecture in relation to regional and urban development. In spite of the book’s flaws, for those who seek a critical reflection on Japan’s most prominent artists since 1990 as well as a primer on the work of their lesser-known peers and successors, Before and After Superflat is a worthwhile start.

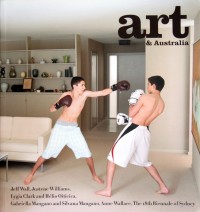

Article on “Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha” in Art & Australia

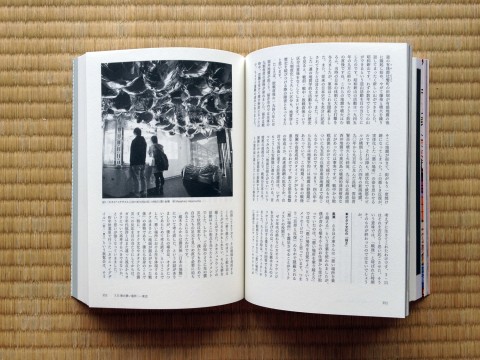

Back in February, I went to Los Angeles to see Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha,” a landmark exhibition of the late-1960s conceptual movement held at Blum & Poe.

The gallery is well-known for having represented Takashi Murakami and Yoshitomo Nara since the 1990s, but in recent years they signed on Lee Ufan, the Mono-ha group’s Korean-Japanese theoretician. Thus, it was a natural progression for Blum & Poe to hold a survey of Mono-ha as a whole—something that has never been attempted in the United States.

“Requiem for the Sun” was, quite frankly, astonishing. Anyone who has studied the movement will mostly have seen only photographic documentation of ephemeral works that have long vanished since their original presentation in the 1960s and ‘70s. Mono-ha is all about the “encounter” with raw materiality, so this exhibition was an invaluable opportunity for viewers to have that essential first-hand experience. The brute presence of installations such as Kishio Suga’s Soft concrete (1970/2012) spoke for itself.

The current issue of the quarterly journal Art & Australia features an article I wrote on “Requiem for the Sun.” In it, I frame the exhibition in terms of a recent surge of international interest in Mono-ha and the postwar Japanese avant-garde. Given that the artists do not “create” their works so much as “present” them, I ask how did the latest “re-presentations” at Blum & Poe compare with past iterations.

Particularly exciting for me was the re-presentation of Nobuo Sekine’s Phase – Mother Earth. Originally made in Kobe in 1968, this piece—a 2.7-meter-deep by 2.2-meter-wide cylindrical hole in the ground with an adjacent monolith of the same proportions—has only been re-presented four times since. The last time was in Tokyo in October 2008, a three-day process that I documented for Tokyo Art Beat. It was intriguing to see Phase – Mother Earth in Blum & Poe’s back yard, surrounded by palm trees. The piece is inherently characterized by the soil from which it is made, so the great majority of us have only seen its dark, earthen character in photos from 1968. In LA, the earth was much grittier and grayer—it felt inherently more “urban.”

You can read reviews of “Requiem for the Sun” on Artforum, Artnet, and the LA Times.

ART iT’s deputy editor Andrew Maerkle has also published Between Potentiality and Fatality, a three-part in-depth interview with Kishio Suga.

Nobumasa Takahashi Illustrates “Tokyo: Portraits and Fictions”

Takahashi Nobumasa, the artist who illustrated Art Space Tokyo, has provided some astounding work for a new book on Tokyo.

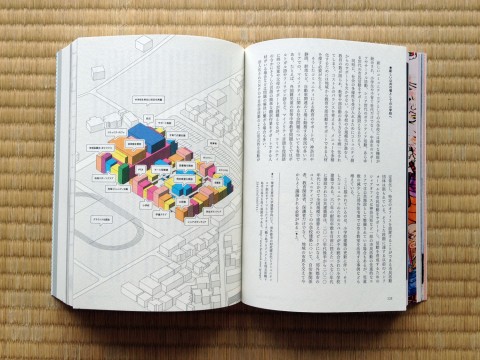

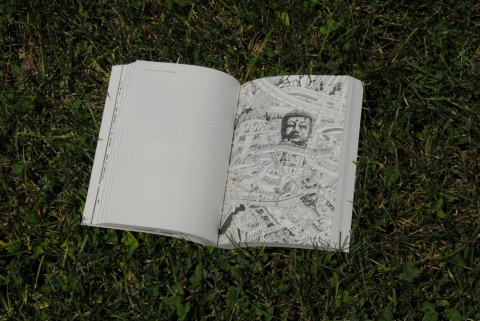

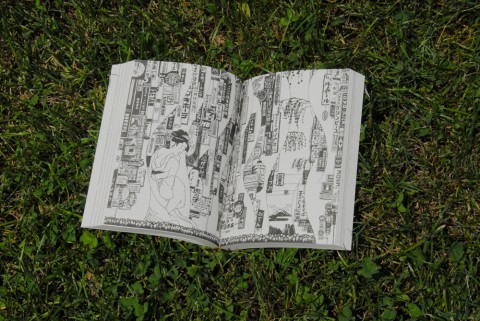

French architect Manuel Tardits’ Tokyo: Portraits and Fictions is a meditation on the urban planning and spatial culture of the Japanese capital. Reminiscent of Roland Barthes’ Empire of Signs (1970), the publication spans the genres of history book, travelogue, and architectural critique. Its 85 chapters are short, eulogistic streams of consciousness that cover concepts and narratives ranging from “Steps” to “Urashima Taro,” “Shadow,” “Ubiquity,” “Enclosures,” “Heroism,” and “Superflat.”

Architects are prone to flowery and overwrought writing, and the text in this book is no exception. What might be a bit of a rushed translation into English also seems to add to the awkwardness in some places. So while one could read the book from start to finish, it may be more pleasant to dip in to it at random intervals and digest it in morsels, one idea at a time.

Takahashi’s pen-and-ink illustrations are as always a playful array of crisp lines, wobbly protrusions, and dense compositions. In his hands, Tokyo is a web of silhouetted telephone lines, a cascade of neon shop signs, and a tangle of elevated expressways and railroads cradling the head of the Giant Buddha of Kamakura.

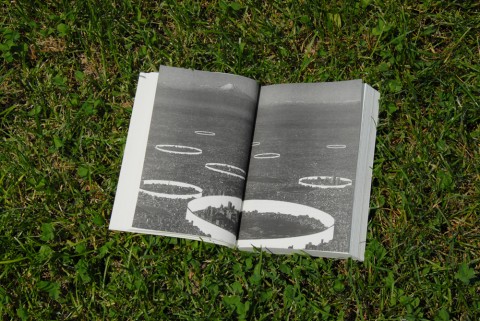

I was also pleased to discover the work of the book’s other illustrator, Stéphane Lagré, a French architect based in Nantes. His grainy photo-collages are an unnerving take on the city. One stands out in particular: a panorama of Tokyo in which Mount Fuji looms large on the horizon and nine white rings ominously encircle different areas of the city. They recall one of the early scenes in Katsuhiro Ohtomo’s Akira (1988), in which the nuclear explosion that destroys Tokyo is depicted as a rapidly expanding dome of light that consumes the metropolis.

ArtAsiaPacific Magazine relaunches its website

ArtAsiaPacific, the leading publication on contemporary art in Asia, the Pacific and the Middle East, relaunched its website this week.

The new site—designed by LinkedBy Air, the team behind the Whitney Museum site’s relaunch last year—makes dozens of past articles available for free, including many on contemporary Japanese art.

The bimonthly magazine will continue to release selected articles with each issue, and there will be regular uploads of web-exclusive reviews, video interviews, news reports and blog posts. Meanwhile, the archives, which currently go back to 2007, will grow over time.

Here is a compilation of links to the articles on contemporary Japanese art currently available on the site. As the 2011–2007 span of the archives happens to coincide with when I started contributing to the magazine from Tokyo and then moved to New York to become a full-time editor, you’ll notice that a chunk of them are my own!

Features

• Daido Moriyama: “Out of the Darkness” by Ashley Rawlings [AAP 70, Sept/Oct 2010]

• Taboos in Postwar Japanese Art: Mutually Assured Decorum by Ashley Rawlings [AAP 65, Sept/Oct 2009]

• Lee Ufan: Illusions and Interrelationships by Ashley Rawlings [AAP 62, Mar/Apr 2009]

• Makoto Aida: No More War; Save Water; Don’t Pollute the Sea by Andrew Maerkle [AAP 59, Jul/Aug 2008]

• Yoko Ono: The Artist in Her Unfinished Avant-Garden by HG Masters [AAP 58, May/Jun 2008]

Essays

• Institutional growth and diversification in the Tokyo art scene: “Living in A Beautiful Japan” by Roger McDonald [AAP 53, May/Jun 2007]

Reviews

• Ryoji Ikeda: “+/- [The Inifinite Between 0 and 1]” at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, by Kenichi Kondo [AAP 64, Jul/Aug 2009]

• “Into the Atomic Sunshine” at Daikanyama Hillside Forum by Ashley Rawlings [AAP 61, Nov/Dec 2008]

• Daido Moriyama: “Retrospective 1965–2005 / Hawaii” at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography by Ashley Rawlings [AAP 60, Sept/Oct 2008]

News

• Controversy over Takashi Murakami’s exhibition at the Château de Versailles by Jina Valentine [AAP 71, Nov/Dec 2010]

• Controversy over Seattle Art Museum guard altering a Yoko Ono work by Rebecca Close [AAP 66, Nov/Dec 2009]

• Yoshitomo Nara’s arrest for writing graffiti in the NYC subway by Hanae Ko [AAP 63, May/Jun 2009]

Art Space Tokyo Reviewed In LEAP Magazine

Happy New Year! We hope you’re as excited about 2011 as we are.

Happy New Year! We hope you’re as excited about 2011 as we are.

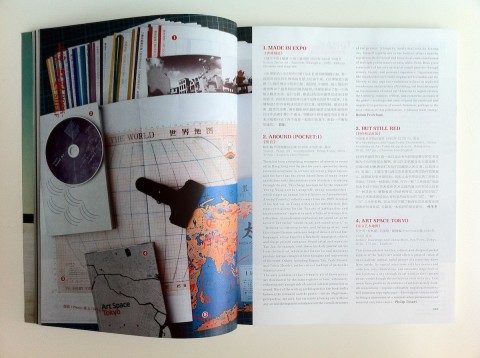

The year has already got off to a good start for us. We just received a copy of the December issue of LEAP, a bilingual Chinese-English periodical on contemporary art in China. In it, its editorial director, Philip Tinari, wrote a brief but glowing review of AST—one that appreciates our enthusiasm for the Tokyo art world, the city and the art of bookmaking.

This immaculately written, edited, and designed pocket archive of the Tokyo art world offers a printed vision of its co-authors’ mental, nodal picture of a scene they know from the inside. Its topical interviews with key dealers and collectors, inky illustrations, and articulate maps don’t so much as portray a city through its art world as they capture an art world through the meticulous voice of its city. Less ironic than gleeful in its embrace of authoritatively bookish conventions—copious endmatter, empirical footnotes, self-conscious copyright page—the compact volume revels in being a monument at a moment when permanence can seem but a stylistic choice.

Thank you, Philip!

Snow Magazine Launches

Following weeks of dropping hints and teasers on his blog, long-time Tokyo-based design writer and editor Jean Snow has finally launched his new online magazine.

Snow magazine offers news and guest-columns covering the cultural landscape of Tokyo and Japan, as well as some syndicated content from the Néojaponisme web journal and Paper Sky magazine. And it’s a joy to look at!

It’s a much-needed successor to PingMag, the popular online design magazine that ceased publication with the recession.

The Tokyo Art Scene in ArtReview

A feature article I wrote on the Tokyo art scene has been published in the October issue of ArtReview.

A feature article I wrote on the Tokyo art scene has been published in the October issue of ArtReview.

In it I talk about the next generation of artists who are defining Japanese art, such as Lieko Shiga, Miwa Yanagi, Kohei Nawa and Izumi Kato, as well as cross-genre exhibitions like last year’s “Space For Your Future”. I also explain how gallery owners like Taka Ishii and Tomio Koyama have cultivated a new generation of dealers out of the former staff of their galleries, such as Jeffrey and Misako Rosen, who set up their own gallery Misako & Rosen in 2006, which is reflective of a broader trend over the past four years.

ArtReview asked the Tokyo-based Swedish photographer Anders Edström to shoot some of the galleries, artists and dealers mentioned in my article, and I was pleasantly surprised by the images when I opened the magazine for the first time. Edström has captured some delightful, informal moments: among them, Jeffrey and Misako Rosen at their gallery between exhibitions, getting paintings ready to hang on the wall, and artist Tomoo Gokita in his studio and out in the street with his mother in the Koenji neighbourhood.

You can read this issue of ArtReview, as well as all of its past issues, by registering for free on its website.

Art Space Tokyo in Art & Antiques Magazine

The October issue of Art & Antiques, a California-based magazine aimed at collectors of all kinds of art, including contemporary art, has a feature on the Tokyo art scene written by Edward M. Gomez.

The October issue of Art & Antiques, a California-based magazine aimed at collectors of all kinds of art, including contemporary art, has a feature on the Tokyo art scene written by Edward M. Gomez.

Covering all kinds of art spaces that art enthusiasts should seek out on a visit to Tokyo, the article also mentions several that are featured in Art Space Tokyo, which Gomez calls “the best insider’s guide in English to the most interesting outposts for cutting-edge art in the Japanese capital”.

Quotes from AST crop up a couple of times in the article, including Tetsuya Ozaki’s views on the instability of the Chinese art market and Masami Shiraishi’s thoughts on how the Tokyo art scene is at its most vibrant in fifteen to twenty years.

Read the article online here.

Thank you Edward!

Japanese Contemporary Art in DAMN˚ Magazine

The next issue of the very slick DAMn˚ magazine (#18), a Belgium-based publication that focuses on contemporary design, art and architecture, will feature a six page article on Japanese contemporary art that I wrote.

The next issue of the very slick DAMn˚ magazine (#18), a Belgium-based publication that focuses on contemporary design, art and architecture, will feature a six page article on Japanese contemporary art that I wrote.

The article is essentially an introduction to the Tokyo contemporary art scene, aimed at those who are still under the impression that it’s all about Takashi Murakami and Yoshitomo Nara. I bring up a couple of other major figures like Naoya Hatakeyama and Tatsuo Miyajima, but more importantly some of the key names from the younger generation of contemporary artists, such as Tomoo Gokita, Izumi Kato and Tabaimo.

The article gives a brief overview of some of the galleries that established themselves in the post-bubble economic slump of the 1990s and how the Tokyo gallery world has developed since the early 2000s, in the shadow of the almost exclusive attention that has been paid to the rise of the Chinese contemporary art scene.

Interview in Ping Mag

A little while back, not long after Art Space Tokyo came out, Verena, the editor of Ping Mag interviewed us about a whole range of issues: from what led us to make the book, to how we made it, what we think of the state of art criticism in Tokyo and the current boom in museum building. We’re very pleased to have such an extensive, bilingual interview on a site with such a large, worldwide readership. You can read the interview in English here, or the Japanese translation of it here.

About & Community

A place to keep abreast of Art Space Tokyo related news, reviews, events and updates.

Art Space Tokyo is a 272 page guide to the Tokyo art world produced and published by Craig Mod & PRE/POST.

It was originally published in 2008 by Chin Music Press.

Current Tokyo exhibitions

Powered by Tokyo Art Beat