News, Reviews, Reports

Mind the Mirror – Reflections on Yayoi Kusama

In the past few years Yayoi Kusama has achieved a stratospheric rise in global recognition, with solo exhibitions at the Hayward Gallery in London, 2010; Ota Fine Arts in Tokyo, 2010; Gagosian Gallery in New York, 2010, and Rome, 2011; Victoria Miro in London, 2010 and 2011; the National Museum of Art, Osaka, in 2011; the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, 2011; the Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane, 2011; and the Tate Modern in London earlier this year. That show is now at the Whitney in New York, where one of the main draws is Fireflies on the Water (2002), a dark room with a shallow pool of water and mirrored walls, filled with dozens of hanging fiber optic threads that glow gently in different colors. This cosmos-like installation is one of Kusama’s most intimate and moving works.

Looking back, one could argue that the renewal of her career began with her solo exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in London in January 2000. It was my first encounter with her work and I loved that show so much I went back three times. It centered on Dots Obsession, a yellow room that was covered in black polka dots, as were the large, suggestively shaped balloons that bobbed around. In the next room, Kusama’s phallic “proliferation” sculptures created a palpable air of psychosexual anxiety. For a nineteen year old who was only just becoming familiar with contemporary Japanese art, Kusama’s obsessive, hallucinogenic worldview felt radically different and alluring. I admire artists who are adept at drawing you into their world, regardless of whether you actually like or identify with what they see. Though in principle the medium shouldn’t matter, immersive installations are often the most direct and compelling way to achieve that kind of blanketing intensity.

But the majority of such all-encompassing installations are tainted with some trace of the outside world. Standing in the corner of the Serpentine installation, I remember looking at the red emergency Exit sign hanging from the ceiling, half hidden by the balloons, and thinking that it was an unfortunate intrusion into the artwork, but that the exhibition organizers had clearly done their best to minimize its impact.

It was curious, then, to visit Kusama’s solo exhibition at the Mori Art Museum in 2004 and experience her installations there. They were so badly compromised by didactic institutional interference that the Serpentine’s little red Exit sign seem artful by comparison. On display was a similar balloon room—red with white polka dots—which had a mirrored wall designed to create an aura of infinity. Yet, affixed to that mirrored wall was a sign warning you not to walk into it. And what remaining suspension of disbelief in the artwork one might have maintained was obliterated by the cleaners who were obsessively sweeping the floor on both the days I visited.

It was curious, then, to visit Kusama’s solo exhibition at the Mori Art Museum in 2004 and experience her installations there. They were so badly compromised by didactic institutional interference that the Serpentine’s little red Exit sign seem artful by comparison. On display was a similar balloon room—red with white polka dots—which had a mirrored wall designed to create an aura of infinity. Yet, affixed to that mirrored wall was a sign warning you not to walk into it. And what remaining suspension of disbelief in the artwork one might have maintained was obliterated by the cleaners who were obsessively sweeping the floor on both the days I visited.

The idea of using mirrors to achieve a sense of limitlessness was better employed in the next piece, You Who Are Getting Obliterated in the Dancing Swarm of Fireflies (2004), which was essentially the same as the version of Fireflies on the Water currently on show at the Whitney but without the pool of water. But again, preoccupations with health and safety regulations trivialized the whole experience. There was security guard was on hand to warn you about the shallow ramp that led you up into the room, and once in there barely a minute would go by without an attendant shining a flashlight toward the exit—just to be on the safe side, you know? The exhibition really jumped the shark a couple of rooms later, where one of the galleries had been filled with hay. “Visitors with olfactory sensitivities should be aware that the following room contains hay,” read the sign at the door. You know there’s a problem when the exhibition display is more obsessive-compulsive than Kusama’s own artwork.

For all the admiration I had for Kusama, the rampant commodification of her work has inevitably detracted from its quality and emotional impact. I have nothing against spin-off merchandise as a subsidiary or derivative element of an artist’s practice—and I’m respectful of artists who clearly use it as a tool of critique in its own right—but the ubiquitous, all-too-easily identifiable motif of Kusama’s polka dots have ended up eclipsing all that is actually interesting and historically significant about her earlier work. The radical, rebellious, messy flower-power aesthetics of the 1960s has been sanitized into poorly made keychains and other paraphernalia for the regular consumer and luxury clothes for the wealthy. Kusama was included in Akasaka Art Flower in 2008, for which artists’ works were installed in various locations in this high-end commercial and residential district of Tokyo. Her Dots Obsession (Day) and Dots Obsession (Night) installations were so badly executed—limp, wrinkled balloons and mounds that weren’t flush with the floor—that it seemed like the artist had simply phoned them in. It was so disappointing that I dedicated a paragraph to ranting about it in the 2008 end-of-year review I wrote for Tokyo Art Beat.

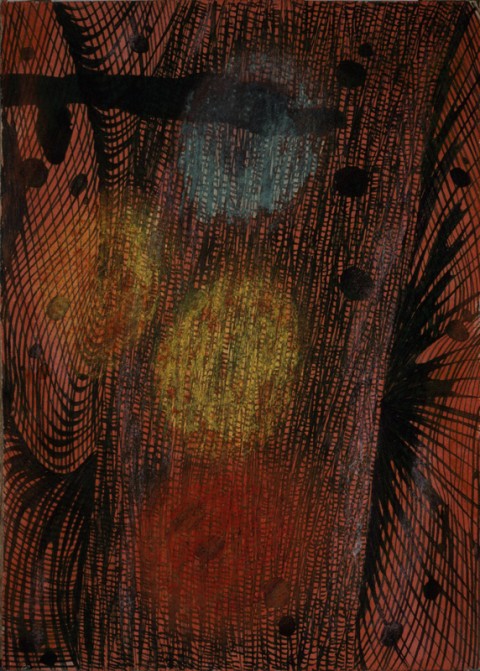

Kusama’s exhibition at the Whitney does a lot to redress this imbalance of spectacle versus artistic integrity. There are no polka-dot balloon installations. Rather, the museum goes out of its way to show the public what it rarely has the chance to see: early works in which you can see the germination of Kusama’s obsessions—dark, absorbing paintings of suns and prickly cell-like organisms. It’s astonishing to think that she was painting these things in the 1950s. These, and the many newspaper and magazine articles from the 1960s that are laid out in display cases are the most compelling aspects of the exhibition. The era in which Kusama asserted herself on the New York art scene comes to life.

I’ve been lucky enough to see beautifully executed versions of Fireflies on the Water twice―once at Gagosian in New York and once at the Louisiana Museum of Art in Denmark―so I didn’t feel too bad about not having time to preorder a timed ticket for the installation at the Whitney. While the rest of the show is open to general admission, visitors are only being allowed into Fireflies on the Water one at a time. You’ll only be allowed one minute in there, but from experience I can tell you that it is absolutely worth it.

About & Community

A place to keep abreast of Art Space Tokyo related news, reviews, events and updates.

Art Space Tokyo is a 272 page guide to the Tokyo art world produced and published by Craig Mod & PRE/POST.

It was originally published in 2008 by Chin Music Press.

Current Tokyo exhibitions

Powered by Tokyo Art Beat